This article was produced and financed by University of Bergen

How do our brains react when income is distributed?

People prefer to get what they – and others – deserve.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Economists from the Norwegian School of Economics (NHH) and brain researchers from the University of Bergen (UiB) have worked together to assess the relationship between fairness, equality, work and money.

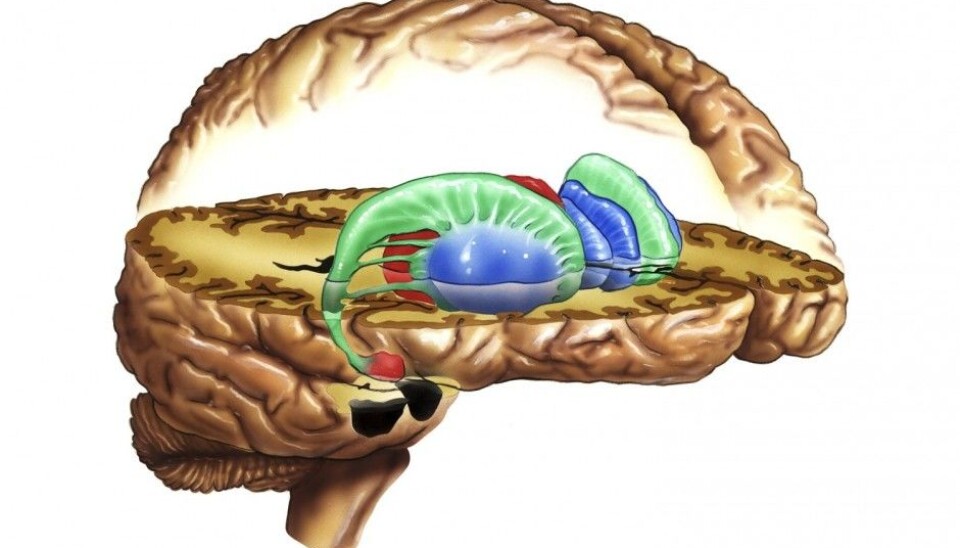

More precisely, the interdisciplinary research team from the two institutions looked at the striatum, the “reward centre” of the brain. By measuring our reaction to questions related to fairness, equality, work and money, this part of the brain may hold some answers to the issue of how we perceive distribution of income.

“The brain appreciates both own reward and fairness. Both influence the activation of the striatum,” says Professor Alexander W. Cappelen. “This may explain why a lot of people are willing to sacrifice monetary rewards when this results in a fairer balance.”

Inequality vs. fairness

Cappelen works at the Department of Economics at NHH and is co-director of the Choice Lab, which consists of researchers devoted to learning more about how people make economic and moral choices.

Along with his NHH Choice Lab colleagues Professor Bertil Tungodden and Professor Erik Ø. Sørensen, Cappelen wanted to explore how the brain’s reward system works. To help them answer this question, the NHH team got in touch with brain researchers Professor Kenneth Hugdahl, Professor Karsten Specht and Professor Tom Eichele, all from the Bergen fMRI Group and UiB’s Department of Biological and Medical Psychology.

Together, the NHH and UiB researchers set out to prove that the brain accepts inequality as long as this inequality is considered fair. The researchers published their results in the article Equity theory and fair inequality: A neuroeconomic study, which was published in the scientific journal PNAS on 13 October 2014.

People’s preferences for income distribution fundamentally affect their behaviour and contribute to shaping important social and political institutions. The study of such preferences has become a major topic in behavioural research in social psychology and economics.

“Our research showed that the striatum shows more activity to monetary rewards when the reward was judged to be fair,” says Kenneth Hugdahl.

Despite the large literature studying preferences for income distribution, there has so far been no direct neuronal evidence of how the brain responds to income distributions when people have made different contributions in terms of work effort.

Inspired by an article in Nature

The background for the joint study between the NHH and UiB researchers was an article in Nature in February 2010, where an interdisciplinary team of American researchers found evidence that people’s brains react negatively to inequality. The American researchers reached their conclusion by studying how the striatum responded to different levels of inequality in a situation where everyone had made the same contribution.

“We wanted to challenge the interpretation of the research results published in Nature. This as other studies have found that people sometimes find income inequality to be fair. In particular, we had shown in several papers, published in both Science and American Economic Review, that people accept inequality in situations where people have made different contributions to the money being distributed,” says Cappelen.

To the Bergen researchers’ knowledge, their PNAS article represents the first neuroimaging study designed to examine how the brain responds to the distribution of income in such situations. As such, and to the researchers’ knowledge, it is also the first study to examine the neuronal basis for equity theory.

Observing the test group

The NHH-UiB researchers put a test group through a set of trials. [For further details, read the section about the researchers’ methodology at the end of this article.]

Their key discovery was that the activation in the striatum in response to receiving more money to themselves depends on how much they have worked. The change in the activation was larger for those who had worked a long time, than it was for those who had worked for a short time.

“We believe this happened because the reward centre was activated by money, but any unfair distribution of money was registered as a reduced reward,” says Karsten Specht.

“The results of our research show that people are neither complete saints who only care about fairness, nor complete egoists who only care about money to themselves,” adds Cappelen.

In what way could the results of your study be beneficial for the greater community?

“It is important to understand the nature of our fairness preferences and when we find inequality fair or unfair, as many political decisions precisely are about this question. Say, if you want the majority to support the ruling tax code, you need to make sure that it coincides with what most people perceive of as fair,” says Alexander W. Cappelen.

The researchers’ methodology

47 male volunteers took part in the experiment. First, the participants were asked to perform simple office work for either 30, 60 or 90 minutes. Participants were then matched in pairs so that a participant who had worked for 30 minutes was paired with a participant who had worked for 90 minutes and a participant who had worked for 60 minutes was paired with a participant who had also worked for 60 minutes.

After this work phase, the participants’ brain activity was measured using an MR scanner. While the striatum’s activity was recorded, the men were presented with 51 different distributions of 1,000 Norwegian kroner or NOK (approximately 118 Euros) between themselves and the participant they were matched with. After each presentation they were asked to evaluate this split.

As an example, a participant who had worked 30 minutes and who was matched with a participant who had worked for 90 minutes was presented with a distribution that gives 120 NOK (approximately 14 Euros) to him and 880 NOK (approximately 104 Euros) to the other participant. He was then asked to rate this distribution on a scale from -5 to +5; with -5 indicating strong dislike whereas +5 indicated a strong liking.

A men only test group was selected for the study because the more similar a group of people is, the easier it is to record any differences in an experiment such as this. According to Cappelen, there is no reason to expect that the effect would have been substantially different if a women only test group had been selected. Previous studies have shown that there is no statistical difference between how women and men experience fairness and inequality.

-----------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Sverre Ole Drønen