An article from Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU)

Caught in the mesh: Scandinavian bears in the road network

Recent research shows that roads pose resistance to movements in Swedish bear populations.

Research from the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU) shows that bear populations are restricted by roads. Ecologists combined new field and analytical methods to identify and estimate the animals' use of a landscape fragmented by roads.

Barriers for the big and small

While roads are practical for people, they are barriers for animals.

Road networks today are so extensive; they affect not only individual animals, but entire wildlife populations. It should hardly come as a surprise that roads hinder small animals, such as rodents, hedgehogs and amphibians, but that our transport networks also pose resistance to the movements of bigger, faster and more mobile species such as the brown bear is unexpected.

"This is the first time we see the effect of such barriers in real time and at this scale for a large carnivore," says NMBU-researcher Richard Bischof, the lead author of the study.

Previous research has documented the effect of barriers on the genetic compositions of animal populations. However, this type of research means that scientists must wait several generations before they can point out the consequences of for example roads. Bischof’s new method allows documentation of contemporary barrier effects as soon as animals in the population begin to experience them.

Large effect of roads

The brown bear is one of the world’s most wide-spread carnivores and inhabits an impressive range of habitats. Despite the bear's great capability to roam, roads represent a distinct, albeit not impenetrable, barrier.

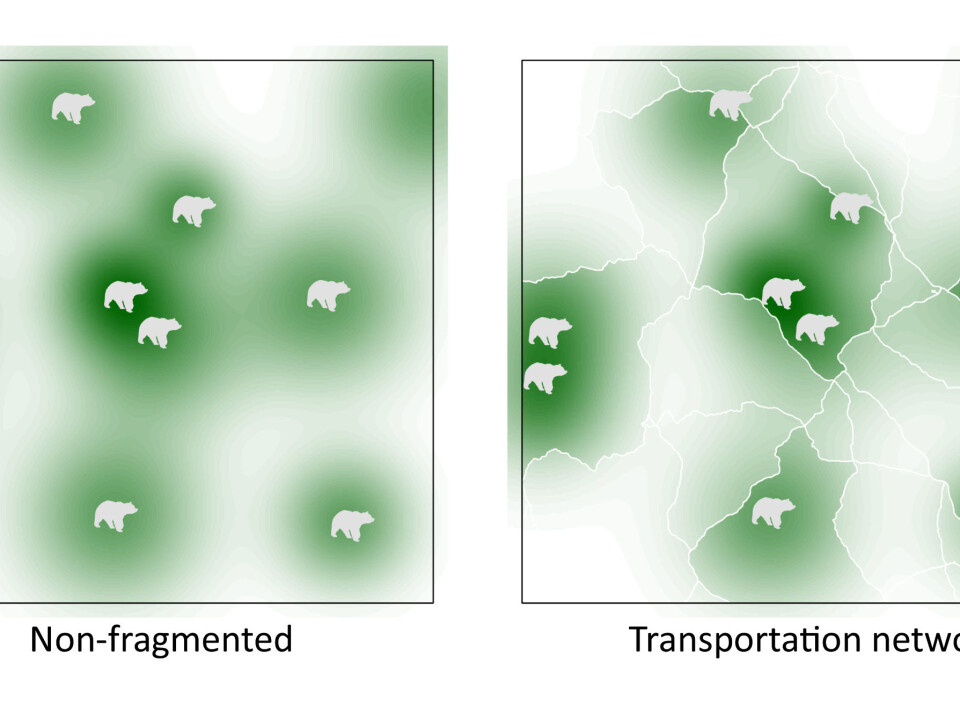

"One can think of a road network as a mosaic of landscape tiles, with each tile surrounded by roads," says Bischof.

The researchers found that bears are reluctant to move beyond the tile in the road network that contains the center of their home range.

Non-invasive genetic sampling

The researchers used DNA-samples to track the bears’ use of landscape. DNA was extracted primarily from feces left behind as the animals moved around.

The information used in the analysis was obtained from Rovbase, an extensive database with monitoring information from large carnivores in Norway and Sweden.

Pioneering models

One of the challenges with the data used in the study is imperfect detection: DNA detected is proof of the presence of a given individual, but not all individuals are detected and not all locations used by bears are identified as such.

The researchers developed an analytical approach that can deal with imperfect detection while making use of the information contained in the spatial configuration of samples.

"Non-invasive genetic sampling allowed us to get a glimpse of the animals' lives without being in physical contact with them," he says.

Shift of focus

Bischof says non-invasive methods such as genetic sampling and camera trapping can complement regular tracking and monitoring in applied wildlife research.

"Aside from the fact that we are less likely to influence animal behavior, one of the advantages of such non-invasive methods is that they allow us to work at the level of populations and landscapes."