This article was produced and financed by The Fram Centre

Little lemmings are monitored from space

The lemmings are small rodents with a big temperament. In some years they lay waste to so much vegetation that the devastation can be seen from space.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

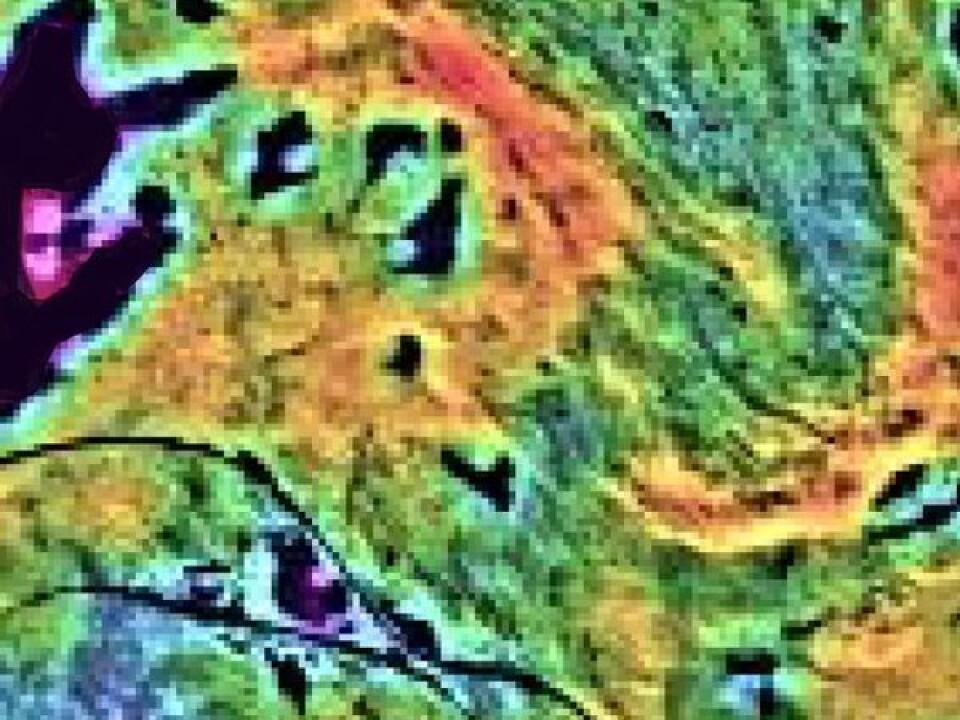

For the first time it has been established that the impact of a ‘lemming year’ is big enough to be observable on satellite images from space.

In an article presented in the journal Nature Climate Change, the research scientists Hans Tømmervik, Johan Olofsson and Terry Callaghan describe the results of their investigation into the impact on the vegetation of large population densities of lemming and vole.

The figures are dramatic. Lemming in particular are capable of eating and destroying between 20 and 100 percent of the vegetation within a localised area, and this destruction occurs beneath the snow in the winter following a peak year for lemming populations, so that the damage only becomes visible the following spring.

“Yes, they actually devour and destroy so much vegetation that it’s visible on satellite images with medium to low spatial resolution,” explains Hans Tømmervik, senior research scientist at the department of the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA) at the Fram Centre in Tromsø.

This is the first time that researchers have been able to determine the extent of a ‘lemming year’ by using data from the MODIS sensor on the US Terra and Aqua satellites, and to see the impacts over an area of 770 square kilometres.

The study shows that vole and lemming reduce the amount of vegetation by between 12 and 24 percent in a peak year with large rodent populations, which is sufficient to be visible on satellite images. However, they also point out that other researchers have reported a 20-100 percent decrease in the plant biomass/vegetation in a peak rodent year, which means that it is probably possible to follow the lemming cycle in large areas across the circumpolar Arctic.

Effects of a warmer climate

The research is based on a series of field observations between 2000 and the end of 2011, carried out both within and without control plots where grazing by lemming, sheep and reindeer was excluded. These observations were again compared with MODIS measurements of normalised difference vegetation index (NDVI) estimates from satellite images.

The study was carried out in the border area between northernmost Sweden and Norway. There were ‘lemming years’ in this area in 2001, 2007 and 2010. All these peak years for lemming coincided with peak years for grey red-backed vole, although it is the lemming cycle that can best be measured from space.

The reason for starting the project was the need to understand the effects of climate change and global warming. The factors that affect the plant biomass must be understood in order to predict the effects of climate change.

Winters with much precipitation and ice can lead to mass death of lemming and vole, which can again have a major impact on populations of predatory mammals and lead to other species such as ptarmigan and black grouse coming under pressure through being hunted in greater numbers by birds of prey and foxes.

"We are now continuing these studies and will focus among other things on the importance of snow and ice conditions for lemming and vole, using snow profile measurements and radar satellite imagery," explains Tømmervik.

Effect on other species

“That lemming and vole have a major impact on the vegetation is nothing new,” he continues. “But our new finding here is that the devastations of lemming and vole are visible from space."

The researchers have also found that lemming and vole affect ‘year-to-year cycles’ in the vegetation’s plant biomass and community composition, which can have a major impact on other species, particularly ptarmigan, hare, reindeer, sheep and predatory mammals, which live in the mountains and the nearby forests.

"It’s of great importance for continuing research that we now have a new tool in the form of satellite monitoring combined with measurements in the field so as to separate out the effects of climate (temperature, precipitation, snow) from other effects such as grazing by lemming, vole and other herbivores," concludes Tømmervik.