Environmental brutes of the past

Have humans ever lived in harmony with nature? Or are we inherently environmental brutes who mindlessly cut down huge forests – and discharge environmental toxins into the soil, the waters and the atmosphere?

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Stories and myths about our relationship to the environment proliferate. The problem is that most of them are wrong.

People have always exploited the resources around them as much as they could, but at the same we’ve been concerned about maintaining a certain degree of natural balance, for a variety of reasons.

Fortunately the technology that can really trigger massive environmental destruction is pretty new, but history is rich with examples of our trashing nature in our vicinity using just primitive methods.

“Humans have been concerned about survival at all times and the margins of existence used to be narrower. People did what they had to do. If they could have disrupted and ruined things more, then they would have done so,” says Finn Erhard Johannessen, a history professor at the University of Oslo.

“The romantic myth of a past when people lived in harmony with nature, contrary to modern mankind who suddenly stumbled off the true path, is utterly wrong,” continues Johannessen.

Chopped down the forest

For instance the forest belt along the west coast of Norway was destroyed in prehistoric times.

“Several theories have circulated about its disappearance and for a long time it was thought that a king had ordered the forest cut to prevent pirates and other undesirables from settling,” says environmental historian Nils Kolle at the University of Bergen.

Another long-lasting belief was that a horrendous storm blew down the large belt of deciduous trees, but research has later shown that most of the forest was cut down.

“This was partly to satisfy the demand for lumber in the late Middle Ages but also to clear the land for pastures,” continues Kolle.

Indigenous peoples in harmony with nature?

A rather deep-rooted and persevering myth is that indigenous populations such as the Samis of Scandinavia, the Amazon Indians and the Maoris of New Zealand traditionally had a much closer relationship with nature than we have today.

“We always hear that indigenous populations were in tune with nature and never used more resources than they needed, but I have serious doubts about that,” says Kolle.

There are plenty of examples of early populations decimating nature and perhaps the worst of these was on Easter Island, which is now well known for its Moai statues.

These stone statues, which flabbergasted the first European visitors, were also the islanders’ downfall. The island was probably settled around the year 1200, and then it was covered by a rich palm forest. But in the course of the next 500 years it became nearly a desert.

The palm forest was chopped down to make scaffolds and frames for the increasingly large Moai statues, and finally this went too far. The demand for more and more and ever larger statues got out of hand, and finally there were no trees for constructing houses or boats.

“In rivalries between clans, erecting a statue offered power and prestige, and the competition got so strong that nobody could stop it,” explains Kolle.

Both myths are wrong

Dolores Jørgensen at the University of Umeå in Sweden has researched ways that European urban societies related to environmental issues in medieval times. She says there are two myths about our relationship to the environment in the old days.

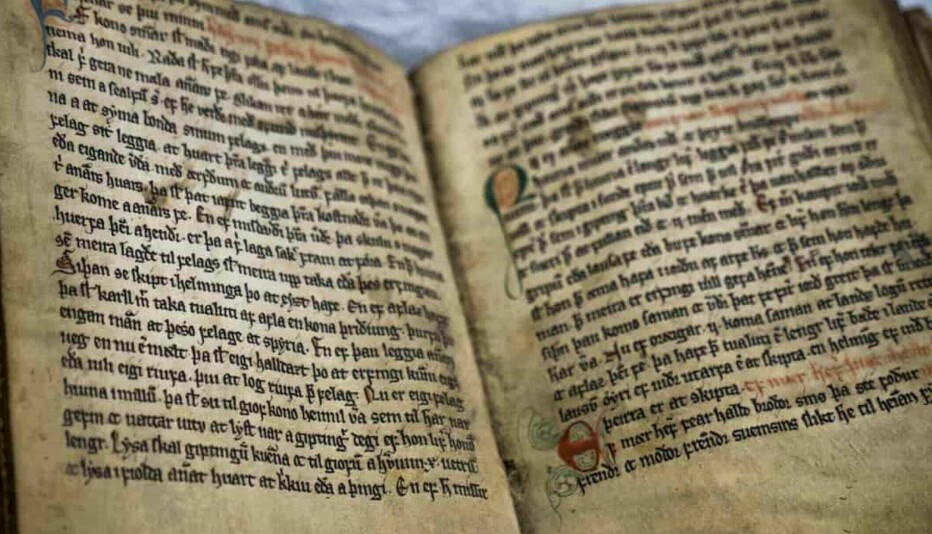

One of them is that we lived in harmony with nature and never did any damage, whereas the other says we were pigs who destroyed everything around us and essentially lived on top of garbage dumps. She thinks they’re both incorrect, and that people in the Middle Ages were actually rather environmentally conscious, only it was in a different way than we are today.

Around the same time that Easter Island was settled, lumber became an important resource in Medieval European towns and cities. Logs weren’t utilised to raise statues, but rather for houses, boats and fuel.

In Europe the property entitlement system was already well-developed and you couldn’t just go out and cut down trees freely in the forests. Forests were either owned or leased and were viewed as resources that were supposed to last.

“At this time it wasn’t a matter of preserving nature for its intrinsic value. A natural landscape was considered wasteful. A dark and dense primal forest wasn’t considered productive.”

Rubbish dumps and street cleaning

In archives from the 1400s we can read that medieval cities started getting concerned about all the trash that was accumulating. Even though they didn’t have any particularly effective industries, livestock produced a lot of waste and there was offal from butchering, leftovers at construction sites and tailings from mines.

In English cities such as Norwich, Coventry and York laws were passed stipulating where residents could establish rubbish tips outside the city walls.

A street cleaning programme was initiated in Stockholm requiring everyone to scrub their sector of the street when a bell was rung. Those who failed to do so were fined.

But the motivation wasn’t concern about the environment. Jørgensen thinks it had more to do with the stench and fears about disease.

“People were concerned about smells in these days. They thought that odours could be the cause of disease and you could be infected through the air.”

So stinky garbage, such as the waste from butcher shops, was ordered to be dumped at tips outside the city walls or in rivers, but the dumping was required to be downstream of the city.

Toxins in the river

Mining operations, tanneries and textile dyeing often produced lots of chemical waste, and elements like lead and arsenic were dumped right into the same rivers that were used for drinking water without anybody understanding the dangers involved.

Actually we didn’t know much about how dangerous lead is or do much about it until the 1980s when the use of the heavy metal was reduced in petrol, paints and water pipes.

Jørgensen says that samples of riverbeds in England show that people of the Middle Ages often drank water with toxic levels of lead.

Lead poisoning is really dangerous, damaging bone marrow, kidneys, the liver, the nerve system and the endocrine system.

If medieval people been more literate and had better lines of communication they would have known that lead poisoning was well documented in the ancient Roman Empire and Greece.

The big connection

The notion of preserving nature simply for its own sake was a phenomenon that started to develop in the 1800s. This is when national parks started to be established, particularly in the USA.

But in the 1960s the environmental movement began in a new guise. This is when nature commenced to being viewed in its entirety and concepts such as Gaia – the living planet – cropped up. By then many generations had generated and lived with substantial industrial pollution.

Environmental historian Nils Kolle mentions a highly polluting smelting plant at Årdal in Norway’s Sogn og Fjordane County, which inflicted severe damage on the local forest. But the major complaint of the local population was that they couldn’t hang their wash out to dry because the air pollution made soiled it.

Saying one thing, doing another

Per Østby, a professor of technological history at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim, says we are more concerned about environmental issues than ever before.

We consider environmental damage less acceptable even though we probably live with a wider variety of environmental problems than ever, particularly when it comes to climate change.

But we often say one thing and do another.

“On the one hand we oppose the development of natural areas, but we still buy expensive cars and continue to pollute, so we’re inconsequential about how we handle this.”

Translated by: Glenn Ostling

External links

- Finn Erhard Johannessen at the University of Oslo

- Nils Kolle at the University of Bergen

- Dolores Jørgensen at Umeå University

- Per Østby at NTNU