More years of education mean a better memory in old age

Public education reforms implemented decades ago are providing new insights. Each additional year of schooling can give mental benefits towards the end of life.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Most everyone agrees that education is important – and not just for instilling knowledge and cultivating the minds of children and adolescents. A host of studies show that more education is linked to better cognitive powers much later in life.

But a lingering question remains.

Is it the length of time spent being educated that provides these benefits later in life? Or are we just seeing that people who are smarter are more likely to spend more years being educated? Or are there other factors that have an impact on both the length of an individual’s education and his or her memory as an senior ?

A new study sheds light on the subject.

Researcher Vegard Skirbekk and colleagues at the International Institute for Applied System Analysis in Austria have examined the effect of an extended education that resulted not from choice, but that was made compulsory at a young age. In short, they looked at school reforms.

Before and after

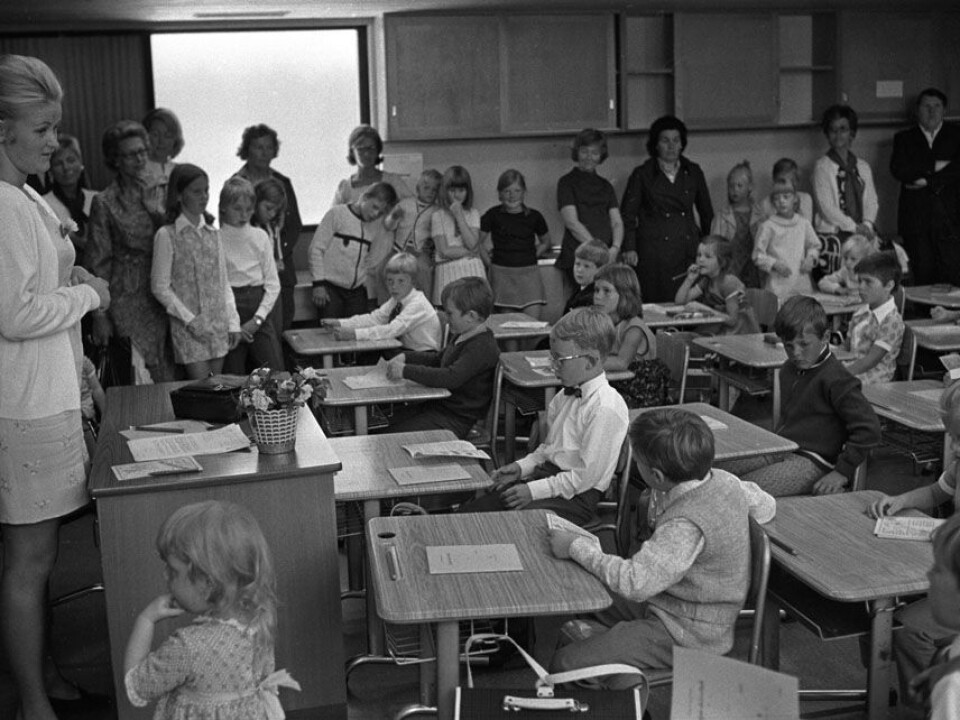

Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany and Italy all implemented school reforms in the 1950s and 1960s, which involved lengthening compulsory primary and secondary school education. An extra year of schooling was added, so a specific age group was more likely to have received a year less of schooling than the kids who attended school after the reform.

If the length of an education really has an impact on retention of memory later in life, then we should see a general change in cognitive abilities among elderly people born just a year or two apart in these countries, because they would have attended less or more school before and after the changes were made, respectively.

A sudden increase in cognitive faculties should also be evident at different times in the countries that were examined comparatively, depending on when their school reforms were implemented.

This is exactly what Skirbekk and his colleagues have looked for, and found.

“We observed a strong positive effect on memory,” says Skirbekk.

“The length of an education really affects cognitive abilities in old age. These results make a great argument for a long compulsory education,” he says.

Better mental function in the north

The figures also indicated that more years of schooling reduced women’s risk of dementia. But there was no improvement with regard to language and comprehension of numbers.

On the other hand, there could be cognitive effects that were not charted in the study, according to Skirbekk.

The reforms also had different impacts from country to country.

“The effect of a longer education was strongest among the countries that initially had the shortest compulsory educations,” says the researcher.

An earlier study has also shown that the elderly in the USA and northern Europe exhibit relatively good cognitive performance compared to their peers in southern Europe, China, India and Mexico. This pattern coincides with the length of compulsory education in the different countries.

Skirbekk thinks several mechanisms may be contributing to the link between longer educations and heightened cognition several decades later.

Learning to learn

Several effects of education may be at play, he says.

Schools give students tangible information that changes their lifestyles over longer periods, affecting their choice of professions, how they participate in the workforce and how healthily they choose to live. But their education could also have altered their brains.

“A student learns to learn, to remember things and to use his or her head. The physiology of the brain is changed. A Swedish study, for one, has shown that thinking actually changes the brain,” says Skirbekk.

Currently we can only speculate about what causes this educational effect. The researcher has no doubts, however, that the phenomenon is real.

Mental ability also has plenty of impact on an individual’s quality of life. Cognitive abilities are related to increases in our job productivity. The average age of the work force will continue to increase in the years to come. Skirbekk thinks that the reduction in productivity that might be expected with an ageing workforce will be delayed by increases in the age at which people retain their cognitive abilities.

Thus, one effect of more years of education could be fewer lost days of work. Moreover, more people will choose to work longer before retiring and collecting pensions.

-----------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling

Scientific links

- Does Education Improve Cognitive Performance Four Decades After School Completion? (Abstract)

- Variation in cognitive functioning as a refined approach to comparing aging across countries. (Abstract)