Wolves won’t save the forest

Wolves have returned to Norwegian forests in greater and greater numbers in recent years. Although wolves mainly prey on moose, researchers have found that the presence of more predators hasn’t cut back on the damage caused by hungry moose.

A new study looks at the potential effect wolves may have in reducing the damage caused by moose on forests in Norway and Sweden.

Moose love leafy trees like birch, rowan and aspen. The Scandinavian “King of the forest” will also happily nibble on the juicy top shoots of smaller pine trees.

The economic consequences of these grazing habits often aren’t known until years later, when the trees are cut. Areas of damaged forest produce low quality lumber, causing enormous losses to the forestry industry.

Do predators cause a cascade effect?

Reintroducing predators like wolves to an ecosystem has been reported to cause what is called a cascade effect. This is when predators alter the food chain several tiers below them.

The most famous example is what happened in Yellowstone National Park in the USA.

This particular story has been popularized in a YouTube video that has been viewed over 40 million times. It describes the introduction of Canadian wolves to the national park in 1995, and how it caused a chain of positive effects for other plants and animals in the ecosystem.

Just like wolves have done with moose in Scandinavia, the Yellowstone wolves immediately began digging into the elk population. Elk love to snack on plants and bushes, including the bushes that grow berries vital to the Yellowstone grizzly bear’s diet.

So when the wolves disappeared in the 1920s and the elk population skyrocketed, there were suddenly a lot less berry bushes to produce berries, which affected both grizzlies and smaller creatures, such as hummingbirds dependent on the nectar from the flowers of berry bushes.

Complicated connections

American researchers have since pointed out that Yellowstone’s ecology is a lot more complicated than is represented in the popular YouTube video, although the wolves do play an important part in it.

However, humans probably have a much larger impact on the ecosystem in Yellowstone than wolves ever could, through increased or decreased hunting. Beavers can cause large changes to the environment around them, as can bears and bison.

Most moose killed by hunters, not wolves

The Norwegian-Swedish study of the relationship between wolves, moose and grazing damage is one of a number of studies that researchers from the Inland Norway University of Applied Science and the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences have recently published.

A related study, for example, describes how many moose wolves in the Norwegian/Swedish population actually kill. The findings show that hunters kill two to three more moose than wolves do.

Humans affect more than wolves

The new study on wolf-moose vegetation was conducted in three Norwegian and six Swedish counties where wolves are found.

For 13 years, researchers recorded the density of moose by tallying moose dung piles, pine pasture damage and the occurrence of roe, aspen, willow and oak. They have also followed wolf population numbers.

The results showed that the wolf has little or no influence on the larger ecosystem overall. Wolves did not affect moose densities, grazing damage to pines, or the diversity of the different species of wood.

Instead, the researchers found that the variation in moose and tree damage was related to factors such as logging, density between trees, distance to the nearest forest road, altitude and snow depth.

The researchers also found that the moose’s choice of forest type was independent of whether there were wolves or not.

No cascade effect

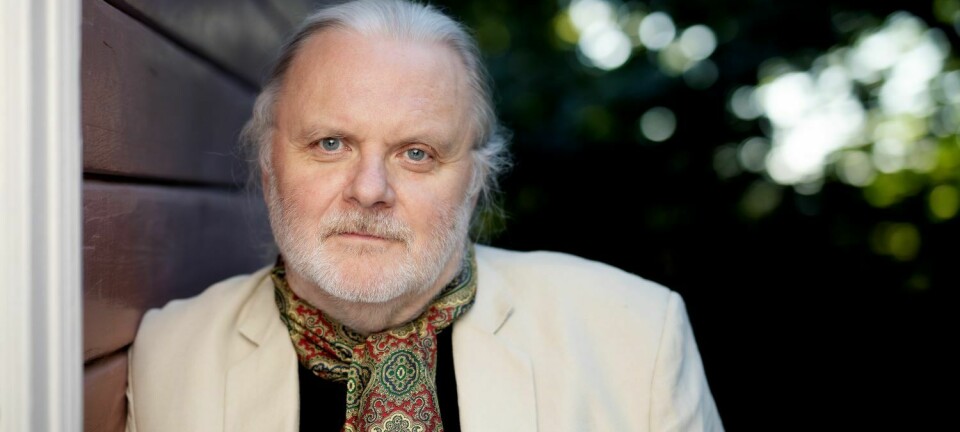

“Our results support the idea that large predators have little potential to create cascade effects at lower levels in the food chain in areas with strong human impact,” said Håkan Sand, a researcher at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in a press release.

He points out that this is typical of many areas of the world where the large predators return.

The fact that the researchers did not find a clear cascade effect from wolves in Scandinavia may also be due to the fact that humans exert high hunting pressure on both predators — wolves — and prey — such as moose.

References:

Håkan Sand et al: “Kan forekomst av ulv redusere elgbeiteskader og øke tettheten av løvtrær? Utredning om ulv og elg del 4” (Can the presence of wolves reduce damage from grazing moose and increase the density of deciduous trees? Part 4 of Wolf and Moose Study) Research report from the Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences. Report (in Norwegian)

Daniel R. MacNulty et al. “The Challenge of Understanding Northern Yellowstone Elk Dynamics after Wolf Reintroduction”, in a special issue on wolves, in Yellowstone Science. Journal pdf.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no