Police forced prostitutes into brothels

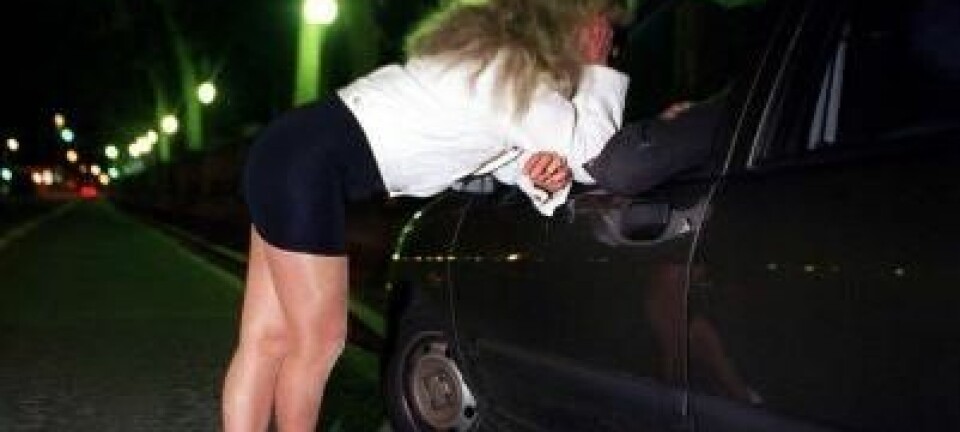

In the 19th century, the Danish government gave indirect consent to prostitution with a law that kept sex workers on a short leash.

In 1863, the Danish police were ordered to keep a close eye on women who sold sex for a living. By 1874, the police could even force the women to sign up at a brothel if they failed to obey police orders.

The battle against sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) played a big part in 19th century police work. It was thought at the time that the cure against these diseases consisted of keeping track of the prostitutes’ health.

”Prostitutes were regarded as a main source of infection for syphilis and other STDs that the state wanted to clamp down on,” says senior researcher Jørgen Mikkelsen, of the Danish State Archives, who has written a journal article on the topic.

The police used their resources on keeping the so-called ‘professional fornication’ under control. But amid growing criticism that this was a way of rubber-stamping paid sex, brothels were banned in Denmark in 1901.

Sex workers punished by whipping

In 1815, the police started keeping a list of prostitutes in Copenhagen and had them checked for STDs once a month. If a woman suffered from e.g. syphilis, she was hospitalised and treated with ointment, and then she was released with a warning never to sell such services again.

This control took place discreetly by order of King Frederick VI, because the order was never announced to the general public.

The reason for this was that the new measures against prostitution and STDs conflicted with the constitution of that time because it implied a general acceptance of sex trading.

”Prostitution was illegal. The man could end up in jail and the woman could be whipped,” says Mikkelsen.

From 1841, the women were checked twice a month. In 1844, this increased to once a week, and by 1853 they were checked twice a week.

And a further tightening coincided with the general restructuring of the police force in 1863. Here, the police were given a special department for inspecting health – including the health of the prostitutes.

Public brothels to prevent clandestine sex trading

The supervision of prostitution climaxed in 1877. Since 1874, the police had had the authority to force prostitutes to register with a brothel if they were caught repeatedly selling sex and were imprisoned.

In the brothels, the police could monitor the woman and make sure that she was checked twice a week for STDs.

But four years later, yet another tightening of the rules was implemented. The rules now applied to all women who sold sex:

- All prostitutes were now required to keep a log.

- The women were not allowed to change their address without prior permission from the Copenhagen Police, as long as the women were selling sex.

- The prostitutes were not allowed to have a boyfriend residing at their address.

- The police had the right to search the prostitutes’ homes.

- Children over the age of four were forcibly removed from the prostitutes’ homes and were placed in foster care. Mikkelsen explains that with this new law, politicians, doctors and lawyers wished to avoid sex trading as a hidden crime. But the clandestine prostitution continued despite the new legislation.

Women married out of prostitution

The police records reveal a great variety in the type of women who were caught selling sexual favours. Many of them only worked the streets for a short period while they were young and until they found another job or got married. Others were professional prostitutes for years, where they sold sex to finance an alcohol-filled lifestyle.

A third group had to make a living from selling sex because they had become unemployed or divorced and thus had no source of income.

Some even told the police that they were selling sex because they liked it.

Varying motives complicate the debate

The police’s control of the women met with increasing criticism from feminists and religious people, who saw this as a way for society to rubber stamp prostitution. The criticism was also targeted at the men who bought these services, because the efforts against prostitution had no consequences for them.

The police lost the authority to force women to sign up at a brothel in 1885, and in 1906 the police also lost the right to force prostitutes to undergo medical examinations and treatment.

“But prostitution remained unpopular. And it wasn’t until 1999 that women’s sex trading became decriminalised. Men have, however, had the same access to buying sex that they have had since 1866, and that’s what we’re discussing today,” says Mikkelsen, noting that the current debate reflects the fact that prostitution is carried out by people just as different and with just as varied motives today as 150 years ago.

------------------------------

Read the Danish version of this article at videnskab.dk

Translated by: Dann Vinther