The epidemic that was wiped out

Smallpox is one of the most devastating diseases known to humanity, but also a great success story of modern medicine.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

”Smallpox has left deep tracks in medical as well as historical literature. These narratives often give a gruesome impression of the epidemic’s devastation.”

Thus begins Peter M. Holst’s section about smallpox in his book on the epidemiology of acute widepread diseases.

Smallpox was one of the most feared and deadliest diseases from antiquity until the last century.

But the disease is now a thing of the past, as the efforts of the World Health Organisation (WHO) led to smallpox declared totally stamped out in 1979. As of 1980 Norway stopped inoculating against smallpox and now most of us give the viral disease no thought whatsoever.

It’s time for a short refresher course on the disease that was called “the most horrific scourge of humanity”.

Contagious and deadly

“Smallpox, or variola major, was feared for two main reasons,” explains Ole Didrik Lærum, professor of medicine at the University of Bergen.

“First because it was a terrible disease with a high mortality rate − at times up to 60 percent of all who contracted it. Secondly it was highly contagious. Sometimes being in a room next door to someone who was infected was all it took.”

Nobody knows when the virus first came to Norway but it’s believed the arrival was between the years 950 and 1200. Lærum says the virus spread like wildfire, by airborne transmission and through physical contact.

“In addition it was a viral disease that localises in the skin, and when blisters or pustules broke, the virus spread to other spots,” he says.

Child killer

In an article of the Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association, S.W. Brochmann writes that Norway was struck by no less than 28 smallpox epidemics between 1676 and 1813.

In the mid-1700s the disease was particularly fierce and children suffered terribly. In her book on epidemics in Norway, Guri Tuft studied church records and found some shocking figures:

In 1741 the number of deaths in Bergen was 1,346 mennesker, and 495 children were born. Most of them died of smallpox. The vicar of Trondheim noted in the following year that over 200 children had died.

The disease was often referred to as the child killer.

Fever, vomiting, rash, cramps

But what was it that killed all these people? According to the history books the answer is as simple as it was horrific: Just about everything you can imagine.

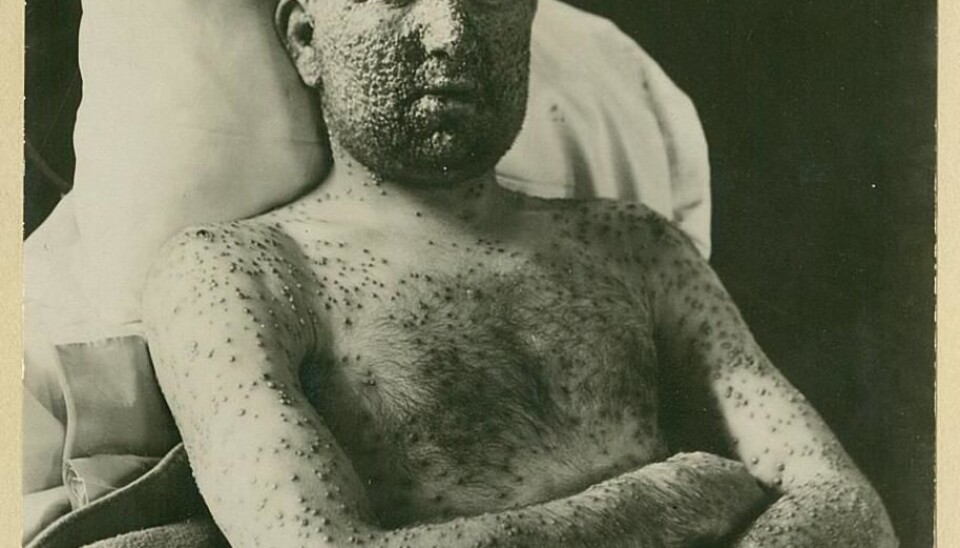

The infected would start by getting very sick, suffering a high fever, vomiting, intense abdominal pains and aches throughout the body. Lower back pain was also common and patients sweated profusely and became groggy. Cramps and fever delirium were other common symptoms.

A rash would then break out as the forerunner of the pox. The rash started on the arms and legs and face and if really bad it would cause bleeding.

According to Holst, if the rash bled the patient often died quickly – before the pox broke out fully.

Then, three or four days after the first symptoms emerged, the patient would appear to improve. The fever dropped and she seemed to be regaining their health.

Unfortunately this was just the quiet before the storm. Now the real onslaught began.

Unbearable pains

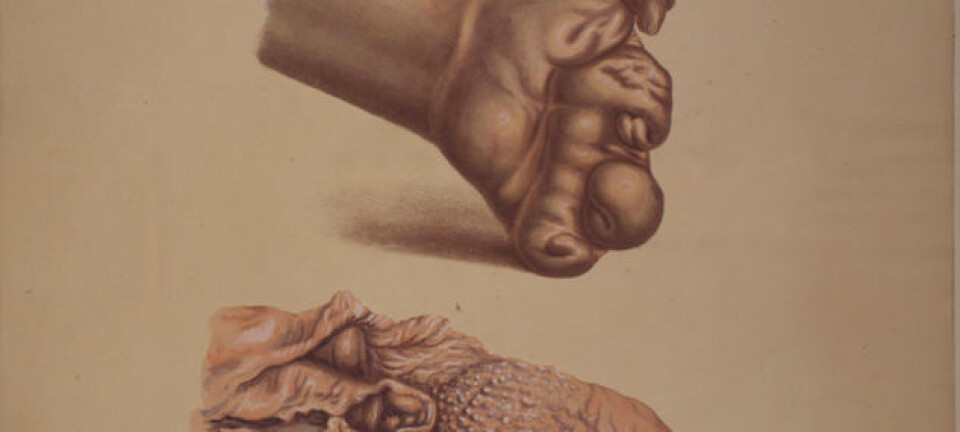

The pox, small pustules filled with liquid, which have given the disease its name, usually broke out six days after the patient got sick. They initially appeared on the forehead and wrists and spread as open sores in the mouth and throat.

Within 24 hours the pox often covered the entire body of a patient.

Eventually the liquid in the pustules changed from clear to an opaque yellow pus and the pustules rose to a size of up to a half centimetre above the skin. Some were so stricken that the pox merged into what looked like a single yellow pustule.

Tuft writes that the pain was excruciating.

Contrary to chickenpox, smallpox spread to the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Patients who weren’t cared for would dehydrate or starve to death because they couldn’t get up.

A cocktail of deadly diseases

A number of complications would follow. Fevers would rise again. Pustules and skin infections beneath facial skin could render the patient unrecognizable, according to Holst.

When pregnant women contracted the disease they usually miscarried.

Another common complication was encephalomyelitis, an acute inflammation of the spinal cord and brain. Not to mention pulmonary infections, inner ear infections, other skin infections, gangrene, paralyses and heart failures.

It’s hard to say which of these symptoms and maladies would be the final cause of death for the unfortunate victims – probably a cocktail of them all.

Frequent epidemics kill the fewest

Because of its maritime connections with the rest of Europe, Bergen was where smallpox first hit Norway. From there the disease spread northwards to mid-Norway and to North Norway, southwards to the rest of Western Norway and South Norway, and finally across the mountains to Eastern Norway.

“When a smallpox outbreak was announced, the alarm spread quickly in the region, but people didn’t know much about contagion in those days,” explains Lærum.

“Right up until the 1800s people believed all kinds of strange things, for instance that smallpox spread as vapours through the air. They called these miasmas, but of course this was pure nonsense.”

After an epidemic subsided, much of the population was immunised, because smallpox, like its feeble cousin chickenpox, usually only infects a person once. So if an epidemic was transmitted relatively frequently from abroad, fewer would die each time.

In such cases the epidemics could have a mortality rate as low as 10 percent.

But if smallpox epidemics broke out less frequently they hit much harder. The population had no immunity, so both rich and poor died like flies. This is also why children were particularly vulnerable.

Youngsters had not lived long enough to build up or establish any immunity, even if the last outbreak was just a few years back, so they died more frequently than adults.

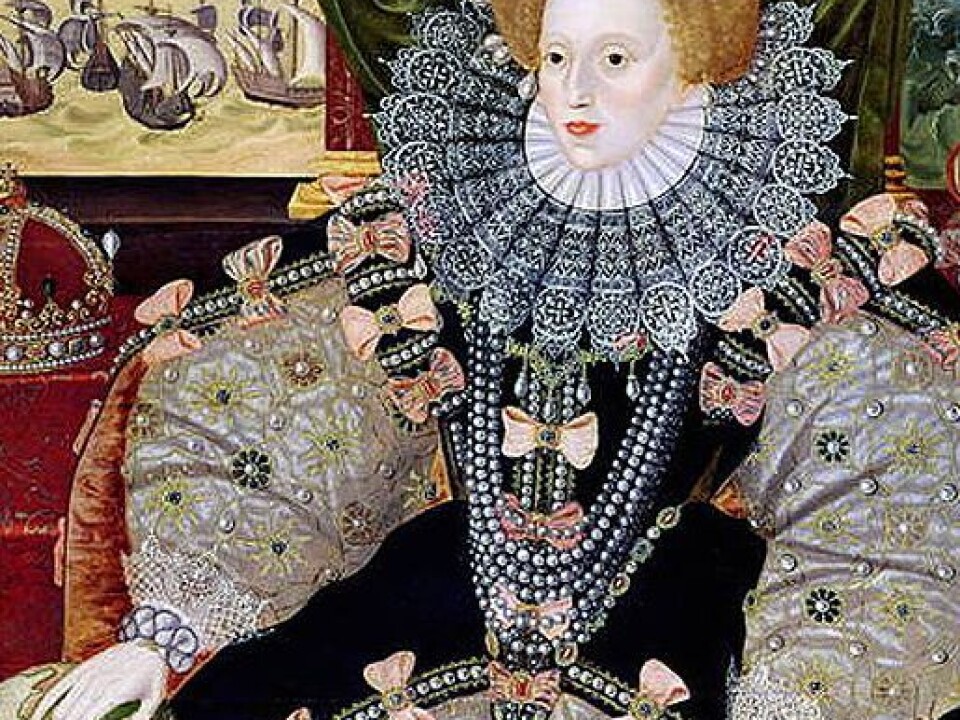

The pockmarked queen

The tribulations of those who survived the disease didn’t stop there.

Smallpox left unsightly scars, or pockmarks, particularly in the face. Many patients were left blind in one or both eyes after their bodies were rid of the virus.

Queen Elizabeth I of England is known for always covering her face with a ghostly white powder. This was an attempt at covering her pockmarks.

“If you were a pirate, however, it was considered an advantage to contract smallpox, that is, if you survived. Then your pockmarks made you look suitably scary,” says Lærum.

Care for some smallpox porridge?

From early on people had a few reasonably adequate solutions for protecting themselves against smallpox.

In the Norwegian valley Østerdalen for instance, people would take the dried pox scabs and mix them in with porridge and feed this to healthy persons.

And a vicar in a town near Oslo, reported that people “bought pox” toward the end of the 1700s. They rubbed a coin on open soars. Then they made a thin cut in the skin of healthy children and attached the coin to the wound. This would give the child a mild attack of the disease.

These remedies may sound disgusting but they weren’t far off the mark − inoculations and finally vaccinations would end the scourge.

Early immunisation attempts

Inoculation is the method in which a healthy child is subjected to smallpox from another person. Pus from an inflicted person was rubbed into the skin of a healthy person. This usually resulted in a milder form of the disease and then the person was immunised.

The first inoculation in Norway was in 1755, and the method proved to be relatively successful. But it was still no guarantee.

Milkmaids provided the final solution.

Eventually a more effective protection was discovered – vaccination. The British physician Edward Jenner noticed milkmaids who had been in contact with a related virus− cowpox − hardly ever died of the human smallpox.

Could the cows’ version protect us against our smallpox?

The answer was yes and in 1801, five years after Jenner’s initial experiment, the surgeon Magnus Andreas Thulstrup carried out the first vaccination against smallpox in Norway. The word vaccination, which now refers to immunisation against all kinds of diseases, comes from the word vacca, Latin for cow.

In 1954 Peter M. Holst wrote: “As we can’t expect vaccination to always protect 100 percent of the population against smallpox, we must conclude the disease will occasionally be imported and spread.”

He was wrong:

Just 25 years later, after an enormous effort by WHO to vaccinate, identify and isolate every case of the disease, smallpox was declared eradicated.

Today the smallpox virus is only known to exist in petri dishes in two laboratories in the world. It is being kept frozen and preserved in case it should make a comeback and we need the raw material for producing vaccines.

Let’s cross our fingers in hope it will never be needed.

—————————————————————-

Read this story in Norwegian at forskning.no