Is train transport the most environmentally friendly way to move goods?

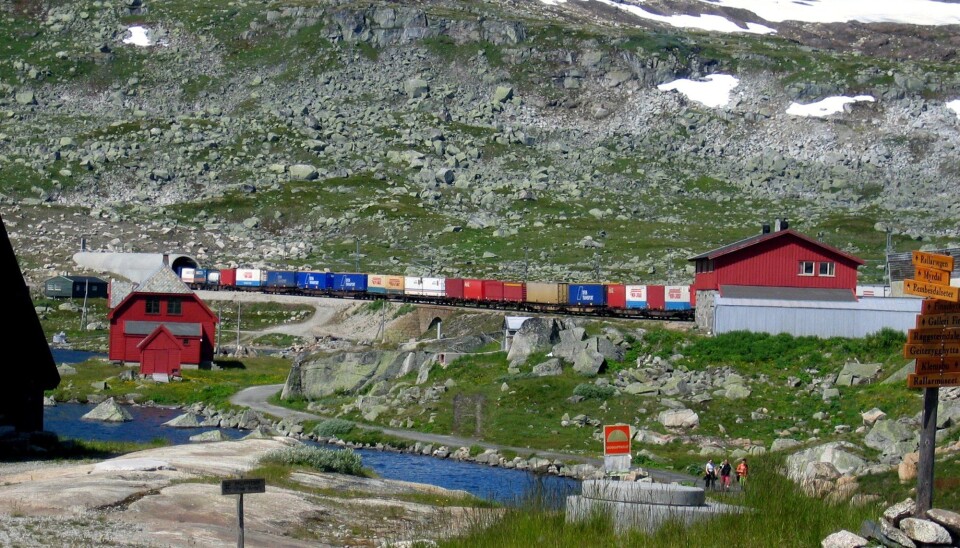

Transporting goods by train instead of trucks can result in big cuts in CO2 emissions.

Travelling by rail is more environmentally friendly than travelling by car. A train trip emits 24 grams of CO2 per kilometre, while a car trip emits 63 grams, according to Framtiden i våre hender (Future in our hands - link in Norwegian).

This is true first and foremost when people are being transported, meaning passenger traffic. But how much CO2 is emitted by the transport of things, such as the goods we buy, eat and fill our homes with?

Researchers have now investigated how much can be saved in CO2 emissions in Norway by shifting 50 per cent of goods that are currently transported by road to the railway.

The study looks at a stretch between Alnabru in Oslo and Bergen, Norway’s second largest city, as an example.

“It will definitely be beneficial for the climate to shift more goods from trucks to trains,” said Linda Ager-Wick Ellingsen, who was one of the authors of the new report.

The report was researched and written by the consulting agency Asplan Viak on behalf of Jernbanealliansen, a lobbying group that wants to promote the use of rail transport in Norway. Ellingsen is now a researcher at the Institute of Transport Economics in Oslo (TØI).

Goods transport to Bergen

Five per cent of Norway’s goods are currently transported by rail. The rest is divided between road and sea, according to figures from Statistics Norway.

The new report shows that there’s a lot of environmental benefit to be gained by shifting goods transport from roads to rails — at least when it comes to the stretch between Alnabru and Bergen.

For those unfamiliar with Norwegian geography, this rail line connects southern Norway and its main cities of Oslo and Bergen in the east and west.

This is also a section where the government has planned a major expansion, called the Ringeriksbanen.

A lot of goods are already being transported on the railway between Alnabru and Bergen: Approximately 1.3 million tonnes of goods travel by train, while 0.7 million tonnes are transported on the E16 and other national roads to Bergen.

More goods on the trains

The researchers calculated CO2 emissions for two different future scenarios.

Under the first scenario, 50 per cent of what is now transported by truck is transferred to trains.

In the second, all goods transport is via roads.

The emissions were calculated over a period of 30 years.

Under the first scenario, Norway would save almost 300,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide in thirty years.

Under the second scenario, if all transport from rail is transferred to road, the country would emit just over 600,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide in the same 30-year period.

In comparison, Norwegian cars and trucks were responsible for 8,000,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions in 2019. And the oil and gas industry emitted 14,000,000 tonnes the same year, according to figures from Statistics Norway.

The report concludes that transporting goods by train instead of truck can contribute to a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

Is it realistic to transfer goods to the railway?

But it’s not all roses and unicorns here: there simply aren’t that many opportunities to transfer goods transport to the railway, according to SINTEF researcher Odd André Hjelkrem.

This is because of the limitations of the existing railway network and the demands for where the goods actually need to go.

With the current railway network as a starting point, the potential to transfer goods from roads to rails is limited to goods that travel the roads that are actually near the railway, Hjelkrem writes in an email to sciencenorway.no.

If it's going to be realistic to transfer half of today's freight transport to the railway, then the railway has to become more competitive both in terms of time and money.

Requires a double track

“A large proportion of transport by rail requires reloading the goods from or to the road at both ends, which takes time,” Hjelkrem writes.

“Also, we have to ensure that freight traffic isn’t lower priority than passenger traffic. And double tracks will have to be built,” he says.

If Norway wants to get the business community to invest in railways as a possible means of transport for their goods, truck transport will have to become more expensive, he says.

“That means the cost of emitting greenhouse gases must increase significantly,” Hjelkrem says.

"But what happens if the truck fleet becomes greener?", Hjelkrem asks.

What about electric trucks?

A greener car fleet is one of the most important arguments for expanding roads in Norway.

More than 50 per cent of new passenger cars today are zero-emission cars, according to the National Transport Plan. And this percentage is due to increase.

But what about trucks and lorries? Will zero-emission versions of electric trucks soon be driving Norwegian roads?

According to TØI’s Ellingsen, it will be a while before there are electric lorries on this stretch of road. But there are already smaller electric trailers that run on batteries and hydrogen.

More likely with more hydrogen cars

Ellingsen believes there will be more filling stations that offer hydrogen by 2025, and that there may thus be more trailers running on it.

She is a little more uncertain about when and if lorries will be electrified.

“If electric freight transport via lorries is going to be possible, it will depend on how far the lorries can travel and how good the charging stations along the different stretches are", Ellingsen said.

“But when it comes to heavy transport, especially over longer distances, we still have a long way to go,” she says.

A look into the crystal ball

These are the kinds of conditions that researchers need to keep in mind when they try to predict the future.

They also have to look at how far the technology has come on electric batteries, how many charging stations and filling stations there will most likely be, and how many electric and hydrogen trucks they think will drive Norwegian roads.

“As a result, there have to be some assumptions and uncertainties when we look into the future like this. A lot can happen with the technology that we cannot predict,” Ellingsen said.

“Nevertheless, our figures give us an indication of how large the emission reductions could be,” she said.

Emissions from building more railway tracks

The researchers included both direct and indirect emissions in their assessment.

Direct emissions are the CO2 that trains and trucks emit when driving, from the combustion of ordinary diesel.

Indirect emissions are everything else that is emitted aside from when the goods are transported.

A truck that runs on hydrogen, for example, still creates emissions related to the production of hydrogen, as well as emissions from building the truck itself.

Indirect emissions also include emissions from the construction of new roads, railways, batteries, maintenance and so on.

“If we’re going to shift more freight transport onto rail lines, the railway must be expanded, which will involve more emissions. Nevertheless, we say in our report that the transfer of goods to rail provides a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions,” Ellingsen said.

For example, the researchers included the emissions from building the Ringeriksbanen in their emissions calculations.

Other benefits of fewer lorries

It is not just the climate that benefits from fewer trucks on the roads.

“Fewer trucks on the roads should lead to less wear and tear on the roadways,” said SINTEF researcher Hjelkrem.

It can also mean fewer accidents between trucks and cars.

“But here the standard of the roads probably has a lot to say in determining the likelihood of accidents,” he said. “For example, there will be less accidents if opposite lanes of travel are separated by a divider, so that there is less likelihood of head-on collisions. If the road is also built to withstand heavy traffic, that can also help reduce accidents.”

“In this case, you then have to look at how much of the road network along the railway has a high-enough standard that consequences in the form of wear and safety can be offset by climate consequences,” he said.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

Reference:

Linda Ager-Wick Ellingsen and Kristine Bjordal: LCA of freight transport track and road. Asplan Viak. April 2021

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no