Does the story of Beowolf explain the Oseberg, Gjellestad and Sutton Hoo ships?

The new Netflix film “The Dig” tells the story of the excavation of the Sutton Hoo ship in England. A Norwegian professor believes that a 1500-year-old poem can explain why a number of large ships were buried during the Viking Age.

The Beowulf poem describes heroes, monsters and dragons who lived in southern Scandinavia a long time ago.

The epic inspired J.R.R. Tolkien to write "Lord of the Rings".

But might it have also been the inspiration behind the burial of large Viking ships in Norway and England? And the construction of the world's largest ship mound in Denmark?

This new Beowulf theory has been proposed by Jan Bill, an expert on ship burials and a professor in the Department of Archaeology at the University of Oslo’s Museum of Cultural History.

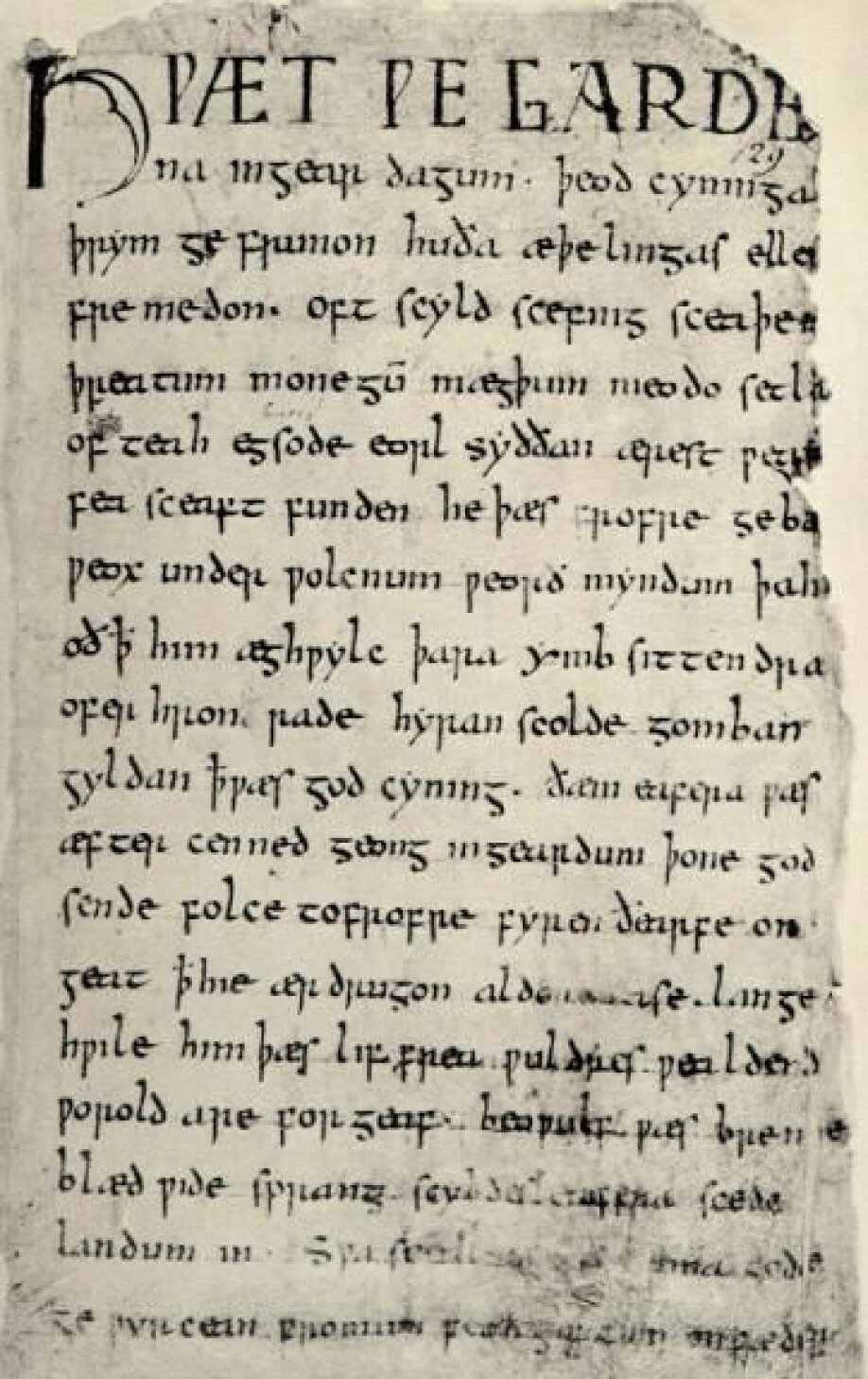

The poem that he contends contains the explanation for the ship burials has more than 3000 lines of verse. It was probably first written down by an unknown poet in England in the 700s.

The ship and the gold helmet

The Netflix movie "The Dig" is based on a novel of the same name. The film has received good reviews. "A beautiful tribute to a bygone era," wrote Aftenposten, one of Norway’s national newspapers. "A refreshingly accurate portrait of archaeology," wrote British archaeologist Roberta Gilchrist in The Conversation.

Both the novel by the author John Preston and Netflix's new film are probably close to what really happened to the people who took part in the dramatic excavation in Sutton Hoo, which was started just as World War II broke out. You can read more about the dig at the British National Trust website.

The mystery of the mounds

Until 1939, what lay beneath the grassy mounds of Sutton Hoo, just outside the city of Ipswich on the north coast of England, had been a mystery.

Mrs. Edith Pretty was a landowner in Sutton Hoo and very interested in archaeology.

She was the one who asked the local "digger" Basil Brown to take a closer look at the largest of the mounds. Eventually, Brown got help from the gardener and animal keeper on the estate.

Inside the mound, the talented amateur archaeologist and his helpers made what are probably Britain's most spectacular archaeological finds ever.

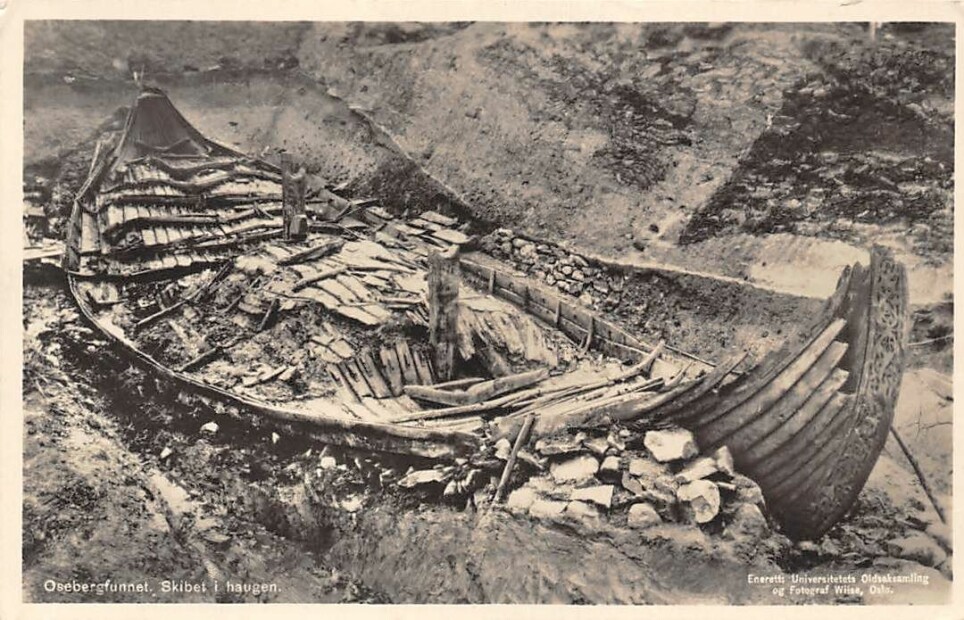

The mound contained a 27-metre-long ship.

In the middle of the ship was a burial chamber full of treasures in silver and gold — including the famous Sutton Hoo helmet.

Why did people make these ship graves?

“The Sutton Hoo ship grave is probably from around the year 625,” Bill from the Museum of Cultural History says.

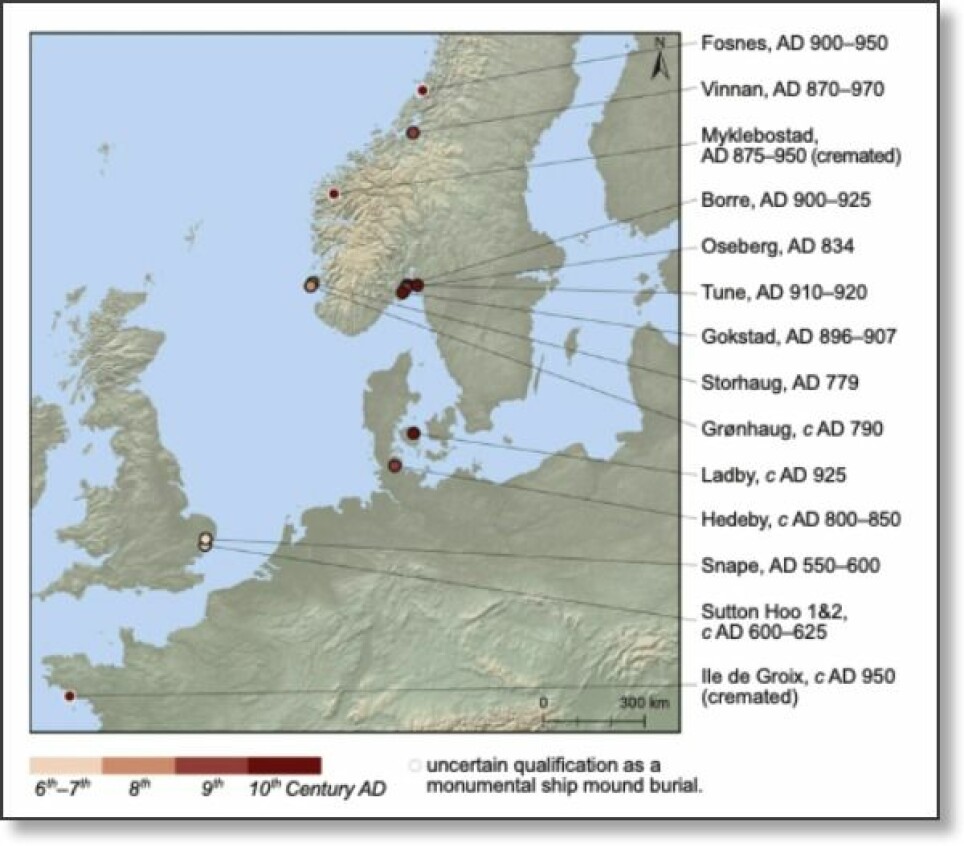

Thus, it is older than both the Oseberg ship burial, which dates from 834, and the slightly newer Gokstad and Tune ships. The newly discovered Gjellestad ship in Østfold may be from around the year 800, Bill believes.

Together, these ships tell us that before the Viking Age, there was a special shipbuilding culture that may have stretched from the British Isles, across Norway and Denmark, to eastern Sweden.

But who built these ships? Who put them in large burial mounds?

And why?

Our problem is that the historians who could have told us about this time — with the Icelandic medieval author Snorre at the forefront— knew little about what happened in Norway and Scandinavia before Harald Fairhair’s time (around 850-930).

Snorre also had to rely on myths and stories. But he probably still knew more than we do.

The Beowulf poem

This is where England's national epic, Beowulf, can help us, Bill says.

His theory is based on a chapter he has written in the new book "Rulership in 1st to 14th century Scandinavia".

According to the epic, the hero Beowulf was born in Götaland in Sweden.

As an adult, he defeated the monster Grendel, who terrorized the Danish king and his men on the island of Zealand.

Later, the hero has to fight a dragon. He kills the dragon, but is so wounded that he dies.

The poem’s details suggest that it was first composed in Scandinavia, perhaps as early as the 6th century. But today we know it from an Anglo - Saxon retelling from the 8th century, which is only preserved in a copy from the early 1000s.

The story of how a royal family came to be

Bill says that the introduction to Beowulf contains the most pertinent information for the Oseberg, Gjellestad and Sutton Hoo ships, and other ship burials.

The introduction describes how a new royal family is created.

It describes a boat with a foreign infant and expensive weapons that comes drifting to the Danish king's coast.

The king adopts the strange child, who will eventually be the next king in the kingdom and thus the ancestor of a completely new royal family.

The child is Odin's son

The Beowulf poem is silent about where the boat with the child comes from. Hundreds of years later, however, the historian Snorre believes he knows:

Skjold, as the child was called, was the son of Odin.

“Thus we have a royal origin myth,” Bill says.

He says that these kinds of myths were common throughout large parts of Europe at the time.

The original myths were used to legitimize royal power.

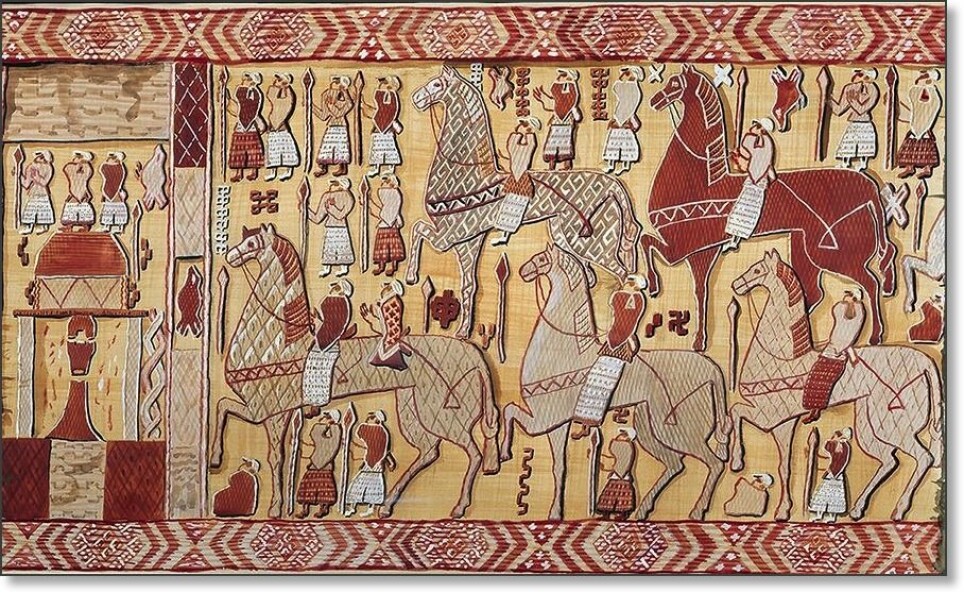

The exciting thing about the Beowulf poem's story about the origins of the famous Danish royal family the Skjolds, is the story of how King Skjold tells his men how they should conduct his own funeral:

In his death, he should be put on a ship, along with magnificent weapons and gifts.

The ship will be pushed out to sea.

This was done, according to the Beowulf poem. And the vessel disappears with the ocean currents.

Bill's theory is that this ship burial story in the Beowolf poem may be the key to the Sutton Hoo and Oseberg ships, and other Nordic and English ship burials.

A ship burial was a confirmation of power

Under this theory, a ship burial was all about showing that the royal family was descended from Odin.

When descendants were linked to the symbolism of monumental ship burials, and thus to the gods, it helped to legitimize the idea that it is these descendants who will rule the kingdom.

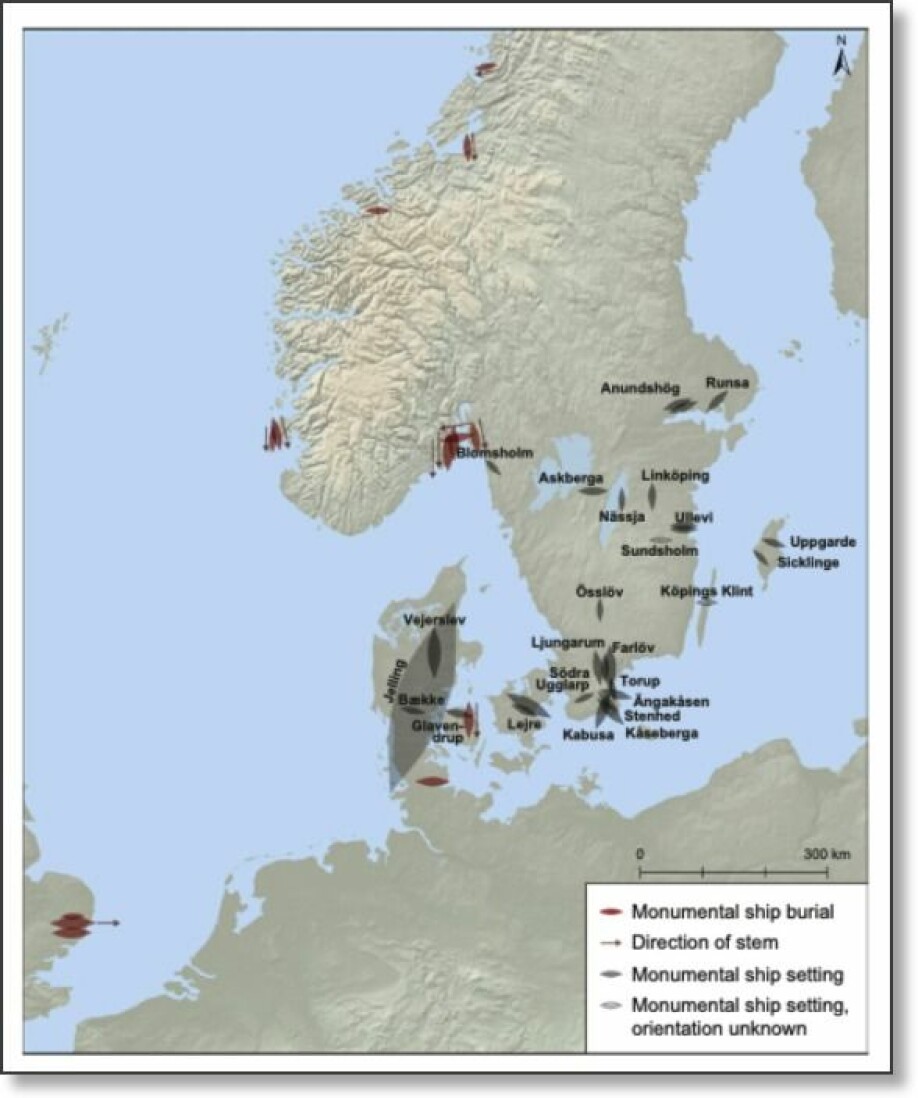

Monumental burials that use ship symbolism first came into use in southern Scandinavia in the 6th century. They then spread to England.

In Denmark and Sweden, huge ship-shaped stone formations, called ship settings, were built. These formed the setting for large cremation bonfires.

Sutton Hoo and later similar sites in Norway didn’t have the labour-intensive giant ship settings that are found in Denmark, Bill said. Instead, real ships were buried with the royals on board, inside large burial mounds.

No matter how the ship's burial was designed, large memorials were left behind in the landscape.

Through these graves, the kings and queens who were buried were linked to the Skjold myth and the story in the Beowulf poem about the royal family with its link to Odin.

“The burial was thus a confirmation that this royal family was qualified to rule,” Bill says.

- RELATED Read about Norway's first Viking ship dig in a century in this story: Layers of soil and turf tell the tale of a grand Viking ship burial

Why were ship graves looted so quickly?

Most royal tombs from the Iron Age and the Viking Age were destroyed long ago, long before any archaeologist managed to put a shovel in the ground.

An important reason why Sutton Hoo is so unique is that no one ever succeeded in looting it.

The graves associated with the Oseberg and Gokstad ships had already been looted as early as the second half of the 10th century, or not very long after the Gokstad ship was buried.

Bill thinks it’s interesting that so many graves had already been destroyed by the Viking Age.

The looting happened while people certainly still knew who was buried in the grave.

They also knew why that person was there.

“The looting of mounds such as the Oseberg ship and the Gokstad ship may have been aimed more at the mound's political message than at the mound's content,” Bill suggests.

The Yngling myth replaces the Skjold myth

In fact, at exactly the same time as the last ships were buried, a new Norwegian origin myth begins to appear in the written sources that exist.

It is the myth of the Yngling lineage, the royal descendants of the god Yngve (also known as Frøy).

The Ynglings first appear in the quatrain Ynglingatal, from around 900. They were probably immigrants from Sweden.

In the Middle Ages, historians linked more or less real Norwegian kings such as Halfdan the Black and Harald Fairhair to the Yngling family. They did the same with people we know actually existed in Viking times, such as Olav Tryggvason and St Olav.

The 10th century in Denmark brought new kings. Gorm the Old and his famous son Harald Bluetooth also relied heavily on the Beowulf myth of King Skjold and his ship. They build a giant ship setting and burial mound in Jelling as a resting place for the king.

The myth of the Yngling had now replaced the myth of the Skjolds.

But Bill believes both were based on the same story about Skjold in the Beowulf poem.

In Norway, the kings were forgotten

“We don’t know who destroyed the Norwegian ship graves,” Bill says.

“But it must have fit nicely into the new Danish kings' plans to present themselves as the real Skjolds, the descendants of Odin, to have Norwegian graves destroyed that used the same symbolism,” the professor said.

In Norway, the looting of the Oseberg ship and the other ship graves led to the extinction of the memory of the royal families associated with them.

“But both in Iceland and in Denmark, historians remembered the ship graves,” Bill said. “They wove them into stories about the past — in Denmark often in association with cremations linked to the Skjold dynasty, and in Iceland as a type of grave for powerful, Norwegian-born emigrants.”

History is not just what is written down

Bill reminds us that history consists of more than was written down and preserved in texts.

Ship burials like Oseberg and Sutton Hoo also tell a story.

“Looking at the archaeological finds and letting them play a major role, even in historical times, can provide completely new and unexpected perspectives on history,” Bill said.

- RELATED And on that note - here's a big question, with a really interesting answer which you may want to read about: Was there a Viking Age in Norway — 2000 years before the Vikings?

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

Reference:

Jan Bill: “The Ship Graves on Kormt – and Beyond”, a chapter in the book “Rulership in 1st to 14th century Scandinavia” (editor: Dagfinn Skre), De Gruyter, 2020. The chapter.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no